American Gothic 2.0 to plant tomato

Added on 29 October 2020

"It's just awe-inspiringly massive," says Kentucky native Jonathan Webb, the company's founder, about the experience of standing inside a space the size of 30 Tesla Gigafactories. Seedlings have already been planted, and by the end of the year, AppHarvest will be shipping the first of what it hopes will be an annual haul of 45 million pounds of fresh, Kentucky-grown tomatoes to grocers including Kroger, Walmart, and Costco. "We're trying to use technology to align with nature and put nature first," Webb says.

As its name suggests, AppHarvest views farming and food through a start-up lens. For Webb, who has a background in the solar industry, the central argument is sustainability. Tomatoes are grown year-round in a climate-controlled, chemical-free greenhouse using hydroponics, robotics, more banks of LED lights than a ballpark, and two species of wasps for natural pest control, resulting in significantly more produce per acre. Strategically placing one of North America's largest greenhouses within a day's drive of 70 percent of the U.S. population means less time between harvest and consumption, ideally resulting in a tastier tomato and less trucking emissions. Nearly $2 billion worth of tomatoes are currently shipped into the United States annually from farms and greenhouses in Mexico.

Webb argues he needs to go big to fight the dystopian farming practices of Big Agriculture, which run ever-larger industrialized operations that emit noxious levels of animal waste and fertilizers. Animals raised on huge CAFOs (concentrated animal feed operations), for instance, live in crowded misery, amid complexes that stain the landscape with so much ammonia and nitrogen, hydrogen sulfide, and methane that children nearby developed elevated levels of asthma. Artificial structures of glass and steel the size of airport terminals can free up the land by concentrating production. It's a pragmatic strain of tech utopianism that asks if the sacrifice of a small portion of the landscape can serve the greater good.

"We have to figure out how to use architecture and design to get the most out of our land and water," he says. "Scientists say we need to feed nine billion people by 2050. It's a real problem."

Connie Migliazzo, a principal and landscape architect with the Portland, Oregon-based firm Prato, who has studied farm ecology and design, says that AppHarvest offers a supersized version of indoor urban gardening, the farm skyscraper rendering turned on its side.

"Monoculture agriculture like App-Harvest is practicing isn't natural," Migliazzo says. "But then again, manipulating plants and planting them in rows isn't natural. The concept of being able to grow food closer to where we need it has myriad benefits, including reduced energy use and higher nutrition intake for the consumer."

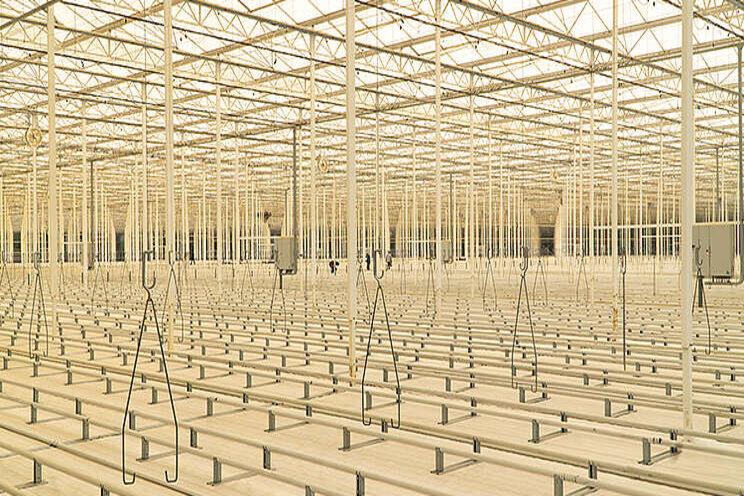

The AppHarvest facility during construction in the summer of 2020. A key argument for this kind of concentrated, tech-heavy agriculture is that it will help keep other land from being developed. Photo courtesy AppHarvest.

While raising crops and livestock has always been an artificial manipulation of the land, the horrors and excesses of corporatized, modern industrialized farming stand out as particularly destructive. The fruit and vegetable industry has greatly consolidated its gains to the richest as the amount of U.S. farmland has shrunk; the most recent U.S. Census of Agriculture from 2017 found that large farms of more than 2,000 acres make up 58 percent of the nation's farms, and the American Farmland Trust says 11 million acres of agricultural land were lost between 2001 and 2016. Mexico's booming tomato industry, sometimes grown in plastic greenhouses, has wrecked local water tables; workers in the Baja Peninsula say their job is akin to "planting the beach."

"Who knows if a Mexican tomato is ultimately better than a Kentucky greenhouse tomato?" says Steven Wolf, an associate professor at Cornell University's department of natural resources, who works on environmental governance and agriculture. "But we are going to see more things like AppHarvest, and not because they're more sustainable. We're going to see more things like this because it's how we maintain plausible deniability. Tomatoes grown out of season by definition aren't sustainable."

A new generation of tech-enabled entrepreneurs believe they've found a healthy middle ground between large-scale production and healthier food, and increasingly have the resources to experiment. AgFunder, a site that tracks investments in the industry, says start-ups raised $19.8 billion last year (AppHarvest has raised $150 million in venture capital funding). Dalsem, the Dutch company that built the AppHarvest site, has built even larger greenhouse facilities in Russia. Iron Ox, based in San Carlos, California, outside San Francisco, has developed a model for growing lettuce that seeks to replace all workers with robotics. The agribusiness giant Tyson Foods recently promoted Dean Banks, the former head of Google's high-tech incubator, to be CEO. And, yes, there's even a greenhouse company called iFarm.

Webb sees the AppHarvest model as ultimately practical. The hydroponic system means water can be run right to the roots of the plants, using 90 percent less water. The entire facility draws from a massive retention pond that will be filled with recycled rainwater (during a storm, the sound of water rushing into the pond sounds like a waterfall). Banks of LED lights will augment the natural cycle of sunlight; plants will "run" for 18 hours a day, bathed in artificial rays. A controlled environment also cuts down on food waste; he predicts the Morehead greenhouse will generate only 3 percent or less food waste. Webb can't tell you exactly how much better it is from an energy and emissions standpoint; several universities in Kentucky have started a life cycle analysis of AppHarvest, but don't have final data. Migliazzo agrees that there are obvious benefits, especially compared to large-scale monoculture.

"It's naive to hang on to the romantic idea that small-scale farms and backyard gardens can feed the world," she says. "The reality is that large-scale agriculture will."

But the negatives are pretty obvious as well. Steel and glass buildings are extremely expensive, Migliazzo says, and greenhouses require a lot of energy for heating and lighting. "Running LED lights nearly around the clock is the most worrisome aspect to me," she says. "Huge buildings with the lights on late at night in rural areas—a glowing orb—could have effects detrimental to wildlife. That's a big red flag to me." (Webb says there will be screens that shield 99 percent of the light, and AppHarvest is currently working with a local utility to build a solar plant to power the facility.)

The 60-acre AppHarvest facility will grow its first crop of tomatoes this year. Photo courtesy AppHarvest.

This kind of model has been tried before, and mostly failed, says Dan Imhoff, an author of numerous books on ecological and agricultural sustainability who's dubious of any claims of energy efficiency. In the 1960s, Spanish growers started an aggressive expansion of protected agriculture near Almeria, a town in Spain's southeast. Decades later, the landscape, nicknamed the mar de plástico, or sea of plastic, after the preferred roofing material for the hundreds of greenhouses, resembles a quilted mosaic from above. Growers have been accused of abusing migrant labor, and the concentrated farming has led to aquifer drainage.

Imhoff says there are relatively few examples of sustainable, year-round, large-scale greenhouse growing. Four Seasons Farm in coastal Maine, run by organic gardening and farming proponent Eliot Coleman, grows vegetables in the winter without the need for artificial heat. Coleman even raises artichokes, he told Mark Bittman of the New York Times, "to make the Californians nervous." He is sought out by many as a mentor owing to his influential philosophy of small-scale farming that prizes soil health and natural resilience as keys to a better harvest.

"Maybe if the AppHarvest model means we're going to save the water table and save the soil and keep carbon in the ground, we're admitting that this is an ecological sacrifice to do something good somewhere else. I'm willing to have that conversation and be open," Imhoff says. "Intensive production here, land preservation over there. But this is factory farming, they're trying to capture a market, trying to make tomatoes like widgets."

The AppHarvest model could help land stewardship, Migliazzo says, if technology can create twice as much food, then use half the land and set the other half aside for projects such as native plantings and pollinator habitats.

The ultimate design and landscape of the AppHarvest site at Morehead is still being determined, says Webb. (The greenhouse takes up only 60 of the site's 366 total acres.) Discussions have focused on creating a "rural landscape that complements our facilities." Options include building an agritech campus, creating minimalist steel and glass buildings for residents (he's met with the architect Bjarke Ingels), parks, stages for acts and activism, or facilities that encourage agritourism.

The interior of AppHarvest's greenhouse, where tomato plants will be planted and harvested, is painted all white to better reflect sunlight and the banks of overhead LED lights. Photo courtesy AppHarvest.

Ultimately, questions about the value of the land are ongoing, a continuing dialogue among business, agriculture, and conservationists. Has the United States reached a point where, to preserve the landscape, we need to invest in the most artificial of agricultural spaces to maintain our food supply? In Mexico, in the decade after the North American Free Trade Agreement passed, the consolidation of Big Agriculture, often in greenhouses, cost 900,000 jobs and shuttered many small farms. Can ultra-efficient, mass operations leave space for small-scale, more regenerative agriculture without putting them out of business?

In the midst of clear evidence of a dereliction of duty to protect such a landscape, AppHarvest argues that the best way forward for farming is to create intricate and immense machines for growing food, removing the pressure to turn more native landscapes into furrowed rows of chemically grown cash crops.

"We have an extremely brittle food system where when something goes wrong, it goes very wrong," Imhoff says. "We're extremely unprepared for what's coming down the pike, and that's because we have embraced food production at a massive industrial scale."

Patrick Sisson is a Los Angeles-based writer and reporter focused on urbanism, architecture, design, and the trends that shape cities.

FROM THE OCTOBER 2020 ISSUE OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE.

Source: Landscape Architecture Magazine

Source: Landscape Architecture Magazine

More news