Before Mars, scientists'll grow space salad

Added on 31 March 2020

In August 2015, Japanese astronaut Kimiya Yui trimmed a few leaves of red romaine lettuce and passed them to NASA astronauts Scott Kelly and Kjell Lindgren. Each drizzled a few drops of dressing onto the precious produce, then popped it directly into their mouths.

"That's awesome, tastes good," Lindgren said.

The International Space Station (ISS) harvest was too scant for a proper space salad, especially since half the crop was sent back to Earth for scientific analysis, but the munchies marked a milestone in human spaceflight. It was the first time an orbiting crop was grown with NASA hardware and then eaten. (Though scientists suspect astronauts might have stolen a few bites from a previous sample.)

We now know that space lettuce doesn't just taste good. It's also safe to eat and as nutritious as lettuce grown back on Earth, according to a new study published in the journal Frontiers in Plant Science.

Lettuce Rejoice

From 2014 to 2016, astronauts grew "Outredgeous" red romaine lettuce inside the ISS Vegetable Production System chambers, or Veggie. Meanwhile, scientists at NASA's Kennedy Space Center ran a control experiment that tried to precisely replicate Veggie's conditions by beaming temperature, humidity and carbon dioxide measurements back to Earth.

When NASA researchers tested both versions of the lettuce, they found the space-grown variety was strikingly similar to the ground-grown controls. Each had equivalent levels of nutrients and antioxidants. Cutting-edge DNA analysis even showed that the space lettuce also developed the same diverse microbial communities as its terrestrial counterpart. Researchers say that caught them by surprise. They'd expected the ISS' unique environment to allow unique microbial communities to thrive there. And neither crops showed signs of potentially problematic bacteria like E. coli.

But researchers say they still have a long way to go before astronauts can help themselves to a cosmic salad bar. This lettuce was a kind of gateway plant. It's easier and faster to grow than most fruiting crops, yet it thrives in similar conditions. Now scientists need to figure out how to nurture slower-growing plants.

"Tomatoes and peppers, which we hope to grow this year and next, will need similar growing conditions. But because they take a lot longer to grow (28 days for mature lettuce verses 80 days for the first fruit from dwarf tomatoes), they are much more of an investment of time and resources," says Kennedy Space Center researcher Christina Khodadad, lead author of the new study.

And while a few bites of lettuce may not draw headlines like the latest rocket test, NASA maintains that humanity's long-term future in space depends on the ability to grow healthy crops there.

"It is very much a concern for a Mars mission, where food may have to be pre-deployed ahead of the crew members and may not be eaten until several years after it was shipped," Khodadad says. "Right now, we cannot guarantee that the diet for a Mars mission will provide all of the nutrients the astronauts will need."

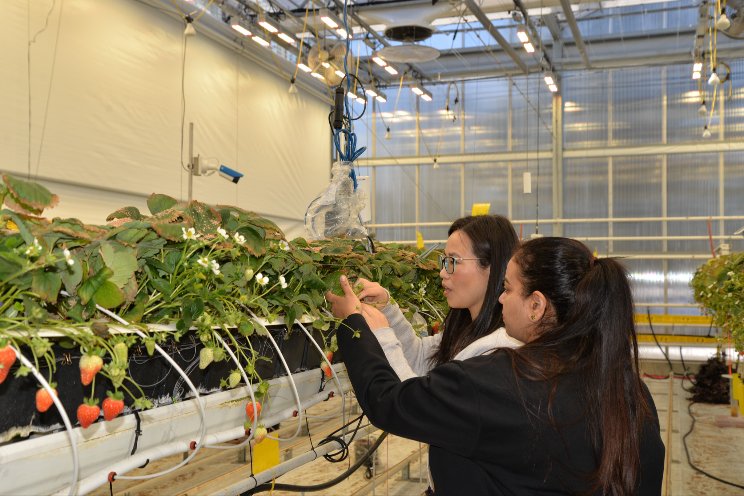

Scientists at the Kennedy Space Center run a control experiment that replicates growing conditions on the International Space Station. (Credit: NASA)

The Cosmic Cafe

Since the dawn of the Space Age, astronauts have survived off processed, prepackaged food. From burritos to shrimp cocktails, these days, ISS is stocked with hundreds of meal options to choose from. But most fresh food remains firmly off the menu. It's not just about satisfying the hankerings for a salad, either.

Prepackaged food has lower levels of some key nutrients, and the ones that are there can degrade over time. That means NASA will have to sort out a supply of fresh food before sending astronauts farther out into the solar system. (Interestingly, the scientists say that some space-grown lettuce actually had higher levels of potassium and minerals, but they caution that their sample size was too small to draw any sweeping conclusions.) Plants could also aid life-support systems on a space colony by sucking up carbon dioxide and pumping out oxygen.

But for all the benefits it offers, space farming presents many challenges.

To start, there's no gravity, soil or rain, and the sun rises 16 times per day. Everything also has to be sent from Earth. In just one week, life on the ISS is hit with a year's worth of radiation on the ground. And then there's the less-obvious challenges.

Without tiny astronaut bees or other pollinators, humans have to take time to carefully monitor the plants and then jump in at exactly the right time to move pollen from flower to flower. Miss the pollination window and you've lost your next crop.

Astronaut Farmers

Scientists have been studying these problems since before NASA even existed. As far back as the 1940s, rocket-borne experiments were sending seeds into space to learn how the radiation changed living tissues. That's decades before humans would experience a microgravity environment. The first serious, long-duration studies were conducted on Russia's Mir space station, which was humanity's first outpost in orbit. There, scientists and cosmonauts spent years experimenting with growing and eating a variety of simple crops.

The results were often troubling.

In joint experiments with NASA, scientists attempted to grow wheat on Mir. Early on, the plants grew excessive numbers of leaves and never flowered. Later tests got the wheat to reach its seed phase, but the seeds proved sterile, perhaps due to a fungus growing on the station that emits a sterility-causing gas. Other plants ended up puny compared to ground controls.

Thanks to some extreme space farming efforts, Mir did eventually manage to grow leafy greens from seed to seed. But even then, the second-generation space crop was weak, perhaps due to disruptions after a resupply capsule collided with the space station.

Growing crops also has been a major focus of science on the ISS over the past two decades. It's now hosted dozens of plant-growing experiments.

And the two Veggie chambers on ISS, together with a more complicated Advanced Plant Habitat, have been designed to take these studies to the next level. Legions of sensors and clearly defined protocols let researchers reduce variables and replicate their experiments. This system also allowed them to steadily build toward farming increasingly complex crops.

NASA astronaut Scott Kelly harvests space-grown zinnias from the Veggie experiment on Valentine's Day 2016. The flowers were a precursor crop to growing other, edible flowering plants, like tomatoes. (Credit: NASA)

NASA astronaut Scott Kelly harvests space-grown zinnias from the Veggie experiment on Valentine's Day 2016. The flowers were a precursor crop to growing other, edible flowering plants, like tomatoes. (Credit: NASA)

Orbiting Peppers and Tomatoes

This August, space farming will see its most challenging crop yet: the chili pepper. Scientists plan to launch seeds of the Espanola Improved Pepper, a fast-growing variety from northern New Mexico that's adapted to shorter growing seasons.

The peppers will be particularly tough to grow, though, because their seeds need two weeks of perfect conditions before they germinate. But they're also scientifically interesting. The pepper genome is far more complex than the tomato's, which could lead to interesting changes in the high-radiation environment of space.

Space peppers could provide a vital source of vitamin C — one several times more potent than citrus. However, it will be a particularly exciting experiment for the astronauts who get to take the first bites. On Earth, these peppers are typically not quite as hot as jalapenos. But it's not clear what will happen to them in orbit.

"Plants often produce the chemical responsible for spiciness, capsaicin, in response to stress," says fellow Kennedy Space Center scientist Matt Romeyn, who's overseeing the pepper experiment. "We currently have no data on how the stress of microgravity could affect capsaicin levels. At the same time, we have grown peppers in the lab that were not stressed at all and the fruit was bland and missing a bit of heat that we were after, so it will be interesting the first time an astronaut bites into a pepper grown on ISS."

By next year, astronauts could be eating fresh tomatoes in orbit, too. That is, once NASA sorts out how to precisely deliver water and nutrients for the 100 days it takes the fruit to reach maturity. The Veggie group says they're still searching for the exact variety to send, but it will be a dwarf tomato adapted for growing in containers. The space agency is even funding some genetic experiments aimed at creating a faster-growing fruit.

"Fresh-picked ripe tomatoes are a rare treat for many, so we thought these would also be a treat for the astronauts," says study co-author Gioia Massa, a Kennedy Space Center scientist working on Veggie.

If they can get them all to grow, astronauts will have the makings of a true space salad.

Source: Discover Magazine

Photo Credit: NASA

Source: Discover Magazine

More news