Confidence in health care essential in fighting virus

Added on 27 April 2020

In every country, the novel coronavirus demands a different approach, development economist Maarten Voors states. 'You could say that there isn't a single outbreak, but two hundred separate outbreaks. The circumstances differ for each country.'

" Invest in the relationship with communities, and gain the people's trust by involving them in their own health care"

Maarten Voors, associate professor of Development Economics

Maarten Voors, associate professor of Development Economics

Voors is currently working on setting up research in Sierra Leone to study the effect of the coronavirus on the economy. In collaboration with colleagues at the local universities, Wageningen scientists have been researching in Sierra Leone for over a decade. Examples of research include studying the impact of development programmes on welfare. The Wageningen researchers were also present in the country during the 2014 Ebola outbreak and were forced to cut their work short and leave the country. Subsequently, they assisted in setting up research programmes on the fight against ebola.

Diligent approach

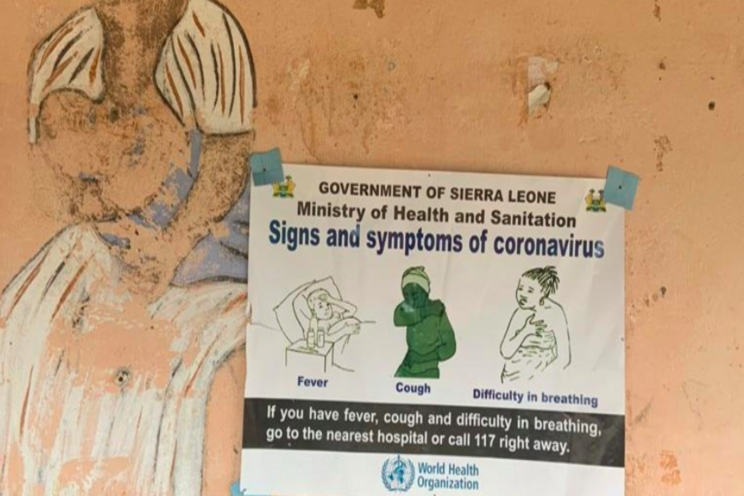

With the current coronavirus epidemic, the government of Sierra Leone reacted rapidly. The country has abundant experience in setting up testing stations, contact tracing and isolation and protection protocols. 'In March, ample time before the first corona infection, Sierra Leone set up extra health checks at its borders and grounded all air traffic. When the first case was reported at the beginning of April, the government started contact tracing, and a three-day lockdown was enforced,' Voors recounts.

Corona recommendations posted at community heath center in Kono District, Sierra Leone (Credit: Kashif Ahmed).

This diligent approach bears fruit. So far, only fifty cases of corona infection have been reported. To curb the spread of the virus, travel, for example, between districts, has been restricted, and events and gatherings are prohibited. And, of course, the well-known recommendations with regard to hand hygiene and social distancing are also in place.

Distrust

'The population accepted the measures immediately', Voors states. This has been vastly different in the past. During the Ebola epidemic six years ago, there was widespread distrust among the population regarding health services. Many people denied the disease's existence. 'At the onset of the outbreak, the government, health services and donor organisations set up large-scale clinics. However, many people refused to get tested, and sick people went into hiding, thus hampering the fight against the disease.'

Improved relations

But, this was not the case everywhere. Thanks to a World Bank-funded programme initiated by the Ministry of Health and several development organisations, some clinics were already working on improved relations with the local population prior to the ebola outbreak. The health workers involved the local community in their work and provided education on health and disease. A study conducted by Wageningen and American researchers later showed that in these clinics, the birth and vaccination rate were higher, and infant mortality rates dropped.

Nurse draws blood for blood tests (Shutterstock).

During the Ebola epidemic, these clinics tested 60 per cent more villagers than other clinics. 'People were much more willing to get tested. Infected patients could be isolated and treated', Voors clarifies. This prevented further spreading of the disease, and, ultimately, lowered the death rate. 'Ebola had an 80 to 90 per cent mortality rate in untreated patients. For patients in hospitals, the mortality rate dropped to approximately 60 per cent.'

Fences and ceremonies

Voors and his colleagues saw similar positive effects during their study on small-scale health centres that the government set up during the epidemic. These temporary facilities, known as community care centres (CCCs) were very small and counted no more than eight beds. The health professionals involved were recruited locally and provided education on the prevention, testing and treatment of ebola. 'The CCCs invested in good relations with the villages. They organised outreach and traditional ceremonies, and are surrounded by fences rather than closed walls,' Voors explains.

Trust the messenger

'The results of this study have implications for how best to invest in health care. It is not just about buildings and equipment. You also need to invest in the relationship with communities, and gain the people's trust by involving them in their own health care', Voors stresses. Local leaders, such as religious leaders and tribal chiefs, also played an essential part in fighting Ebola, because they already hold the trust of their community. 'The more you trust the messenger, the more you will trust the message. Governments must be aware of what they communicate, and through which channels.'

A mandatory hand washing station using a "Veronica bucket" (Credit: Kashif Ahmed)

Responsible citizens

The lessons learnt in Sierra Leone are more relevant now than ever, including in countries such as the US, where many citizens distrust science and the government. This is why local communities in the US should be involved in combating the coronavirus; two of Voors' colleagues write in the New York Times. In the Netherlands, things are different. 'The Netherlands has an extensive social safety net, and there is a high level of confidence in the government and experts. The government leans on individual responsibility and has opted for an intelligent lockdown. Volunteer organisations, shop owner associations and local and religious communities have acted responsibly and offered all sorts of assistance', Voors states.

Less support

In African countries, health care is often less well-organised than in countries in the West. Thus, the experiences that Sierra Leone has in, for example, contact tracing and the use of community care centres, could make a big difference. Nonetheless, the economic impact of the corona outbreak is expected to hit this continent hard. 'The entire world economy will collapse. Fewer funds will be available for developing countries, where there is hardly any form of social security for the population. Preliminary calculations show that half a billion people could fall into poverty', Voors explains. Especially small businesses and those dependent on day-labour with no security of employment will be affected. Voors: 'Many people will return to the rural areas, as is already the case in India. In rural areas, people can resort to subsistence farming. But they also need soap, salt, medicines and money for schooling.'

A woman in rural Sierra Leone, outside Freetown (Shutterstock).

Insight

Voors is concerned for Sierra Leone. 'It is one of the poorest countries in the world, and the government is largely dependent on aid. That will only increase now.' In consultation with the Sierra Leone Ministry of Economic Affairs, and in collaboration with an international research team, Voors will study the effect the corona crisis has on the economic situation of households and businesses. 'We are currently setting up a phone survey for the capital, Freetown, and semi-rural areas. The results will provide the government and donor organisations with insights into how best to support and help the communities and citizens.'

Source and Photo Courtesy of Wageningen University & Research

Source: Wageningen University & Research

More news