Large-scale kelp farm to be developed

Added on 12 November 2020

1. Tell us about the origins of this business venture.

I was inspired by a lecture by Tim Flannery, a famous Australian scientist, originally a mammalogist who explored and authored books about remote parts of Papua New Guinea and Irian Jaya in the 1980s. He is vocal about how seaweed cultivation and afforestation can counter climate change.

I looked at seaweed through the critical lens of scale, innovation and market and concluded that a lot of the seaweed industry is still operating in much the same way as it did in the 1700s: very manual, labour intensive, completely seasonal. It struck me that there had to be a better way, not only technically and economically, but a way that could put seaweed to work as a foundation species for wildlife. As an avid seaman, fisherman, snorkeler and free-diver, I was fascinated by this concept of restoring the oceans, of providing a sheltered ecosystem for diverse species while drawing down huge amounts of CO2.

To provide artificially assisted kelp forests on such a scale to positively impact ocean abundance and health, biodiversity, fish stocks and CO2, it would have to be profitable to unleash yield-seeking capital.

We chose Namibia because of the Benguela current, which is nutrient-rich with stable temperatures and relatively low storm waves (the keyword here is "relatively"). Namibia is also keen to stimulate investment in the blue economy and coastal communities like Lüderitz.

2. What is the current status of the project?

We submitted our environmental impact assessment at the beginning of September and the attendant licence application recently. We're hopeful that they will be positively received.

On the funding front, we have in-principle funding from Climate Fund Managers and Eos Capital for the first five years of operations, which is an enormous vote of confidence. The budget for those five years is forecast at $60 million, which represents a very significant foreign direct investment into Namibia.

3. What are the primary uses of kelp?

Fresh kelp is a highly valued feed for aquaculture, notably abalone farming. Dried and milled, it improves the soil and water retention in dry areas and brings essential micronutrients and bio-actives that improve plant resilience against stresses. Liquid extracts are used as plant protection products, fertilisers and bio-stimulants. Extracted alginate - an ecologically friendly, vegan substitute for gelatin - is used as a thickener/texturiser in toothpaste, ice cream, beer foam and shampoo. It is also used to produce wound dressings and special pharmaceutical fibres as it has anti-inflammatory and anti-viral properties. Scientists have long been using it as a successful treatment for cystic fibrosis; it's the same clogging of the lungs that is the cause of death with Covid-19 and trials are underway to assess it as a treatment.

Other pharmaceuticals extracted from kelp include fucoidan, which improves the immune response of a vaccine, and fucoxanthin, a carotenoid that stimulates fat-burning.

We are also researching other applications, such as high-quality fibres for textiles from seaweed cellulose and alginate. We hope to produce textiles that have a beneficial environmental footprint.

Seaweed has multiple health benefits as a feed supplement for ruminants, from antivirals and anti-inflammatories to a measurable improvement in probiotic gut health and anti-methanogenic activity, reducing cattle's greenhouse gas emissions by up to 90%.

In Asia, kelp is also consumed by humans in many different ways - fresh, pickled, fried, roasted, as seasoning and as a salt substitute - though we are not focusing on this market much at this stage.

4. Take us through the kelp cultivation process.

Seaweeds reproduce by releasing millions of male and female spores each day. If they land close to each other, they reproduce and form eggs that germinate into plants. This process is carried out in a laboratory to produce small plants that are encouraged to adhere to a thin cotton twine. Once they are a few millimetres, we take the twine out to sea and tie it to the installed substrate 20 metres below the surface. The plants grow incredibly quickly, reaching the surface in less than four months and full size (of about 50-60 metres) in six to seven months.

These form vast dense forests of kelp that teem with wildlife. Since sardines and other small fish spawn in wild kelp forests, we are confident our kelp forests will have a positive effect on the fish stocks in the Benguela. We may even contribute to massive sardine schools of the past repopulating the Benguela, with all the positive effects of that on the ecosystem and the fishing economy.

5. How is the kelp harvested?

We use a large combine harvester to trim the canopy just below the surface. The rest of the forest remains an untouched sanctuary for marine life and the canopy regrows every three to four months.

Interestingly, this process of kelp cutting by harvester vessel was developed by the American Hercules Powder Company, in 1915, in California. At that time, the Allied armies fighting the Germans were running out of smokeless cordite for their artillery as the cordite was made from potassium which came almost exclusively from German salt mines. The Royal Navy turned to seaweed as an ancient source of potassium (the word potash comes from the habit of burning the seaweed in big pots and using the ash as fertiliser: pot-ash). The Americans designed and built these revolutionary harvest vessels in six months. They then devised an enzymatic extraction method to get the potassium from the kelp and supplied the Allied armies with cordite from 1916 until 1918.

We will harvest and process the seaweed in Namibia for sale locally and internationally. We are hoping to carry out the vessel conversions in Walvis Bay.

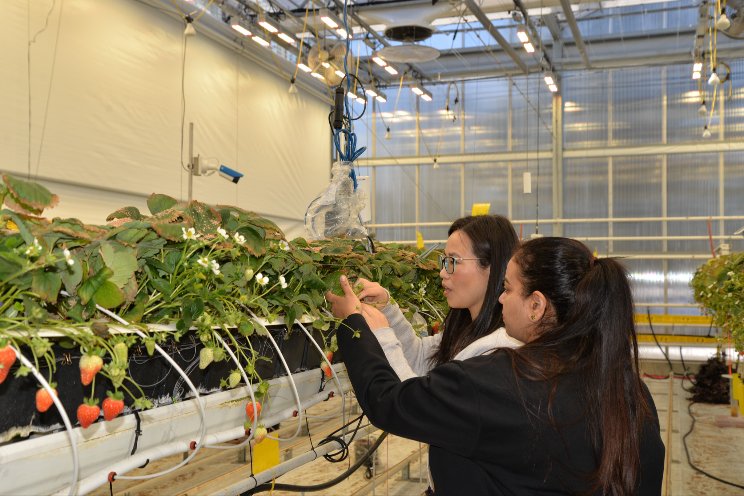

The kelp farm will be located near the town of Lu?deritz in Namibia. Photo Courtesy of Ag News

6. How prevalent is kelp farming in the rest of the world?

The vast majority is in Asia, focused on human food and dependent on low labour costs. Another important centre of seaweed cultivation (red seaweed not kelp) is Indonesia and the Philippines, used for extracting carrageenan (another gelatin-substitute/food thickener). In Europe and North America, seaweed farming is becoming popular, although costs are too high to make it economical.

Our farming is unique: it's on a bigger scale and is focused on a perennial species, creating a forest that thrives with other flora and fauna and one you trim rather than harvest completely. The cold, nutrient-rich water Benguela current means our forests thrive and grow all year.

7. What are the biggest challenges associated with a successful kelp farm?

Without a doubt, the force of the ocean during storms is our biggest challenge. Then there is the challenge of all innovations - when you're trying to do something new, people are nervous about change. We are extraordinarily blessed with an enormous amount of positivity, goodwill and support. Working on something so beneficial for the environment, the coastal communities, academia, marine protected areas, our stakeholders and our investors make it all enjoyable and rewarding.

Header photo courtesy of CERES

Source: Ag News

Source: Ag News

More news