Promise of bio-pesticides

Added on 21 April 2020

The roots of sorghum exude a chemical called sorgoleone, a natural herbicide that kills weeds and other vegetation near the sorghum plant.

For the last 20 years, Baerson has identified the genes and enzymes involved in producing sorgoleone and he's learning how sorghum is immune to the herbicide.

"Fungi do this a lot, too. They're always in this chemical warfare with each other," said Baerson, who works in the Natural Products Utilization Research Centre for the USDA.

"(They) produce toxins that are poisonous to other organisms."

People who work in the crop protection industry usually avoid the word "toxin".

But executives with crop protection firms have become comfortable using other words to describe the naturally occurring toxins found in fungi and plants.

The words they now use are bio-fungicide, bio-herbicide or bio-control products.

Major players like Bayer and start-up companies are spending billions to identify fungi, bacteria and organic compounds in plants that can control the pests (weeds, insects and diseases) that plague producers of wheat, canola, potatoes, apples and other crops.

One such company is Marrone Bio Innovations of Davis, California.

"MBI has screened over 18,000 micro-organisms and 350 plant extracts… to rapidly develop seven product lines (mostly bio-fungicides and bio-insecticides)," the firm says in its news releases.

In November, MBI said it has developed a bio-herbicide that's effective against Palmer amaranth — one of the most aggressive and problematic weeds in America.

Such claims are often made public, as companies in North America, Europe and China are eager to tap into an emerging crop production market.

"The global biopesticides market size was valued at US$3.36 billion in 2017 (and) is projected to reach $10.19 billion by the end of 2025, exhibiting a (growth rate) of 14.93 percent during the forecast period," said Fortune Business Insights, in a 2019 report.

Despite such rosy forecasts, many questions surround biopesticides. Can they perform on big acreage farms? Will they be effective in harsh climates like Western Canada?

And, big picture, can they replace synthetic chemicals in production agriculture?

"Absolutely. Absolutely," said Scott Walker, who lives in Brandon and runs a consulting firm specializing in the research and development of bio-pesticides and biological stimulants.

"As a guy that's in on a lot of different projects… I've seen the results. These things will become a major part of (pest control). The mainline companies, they do have biological pesticides in the pipeline…. They are coming."

Bio-pesticides are not new.

In the 1970s, private companies and scientists were studying soil fungi, bacteria and natural compounds in plants to see if the products could control weeds and other crop pests.

Then, Monsanto unveiled a novel herbicide.

"When glyphosate came out, Roundup was such a game-changer that it had a significant effect on a lot of research effort by companies," said Clarence Swanton, a University of Guelph weed scientist. "A lot of their natural product research… they dismantled it."

Major companies may have shifted their research priorities, but many private and public scientists continued to study bio-fungicides, bio-herbicides and bio-insecticides.

Their research led to new products and new active ingredients.

"Currently, there are about 100 commercially available and registered biopesticides for the control of fungal and bacterial plant diseases," said Antonet Svircev, an Agriculture Canada scientist in Vineland, Ont. "(The) majority of the biopesticides that control fungal plant diseases belong to two bacterial genera (Bacillus and Pseudomonas) and the fungal genus, Trichoderma."

They may be available, but biopesticides remain a small part of the crop protection industry. In general, they're less effective than synthetic pesticides, harder to use and typically more expensive. Consequently, farmer interest has been somewhere between tepid and non-existent.

That attitude is changing.

Weeds, insects and fungal pathogens have become resistant to traditional pesticides and growers are struggling to control pests.

"Weeds have evolved resistance to 23 of the 26 known herbicide modes of action and to 167 different herbicides," says Marrone Bio Innovations.

In addition, millennials and younger consumers are less accepting of pesticides. They are opting for organic foods or anything that comes with a "natural" label.

It's also expensive to develop a new pesticide and get it to market. It could cost $200-$300 million, or more, depending on the product.

Creating a biopesticide and commercializing the product is not nearly as expensive. It's more like $20 million, said Colin Bletsky, chief operating officer of MustGrow Biologics Corp.

The Saskatoon company holds patents for a bio-pesticide made from natural chemicals found in mustard seeds.

Brassica crops like mustard produce sulfur containing compounds known as glucosinolates. The two important compounds that MustGrow uses are sinigrin, a glucosinolate, and myrosinase, an enzyme.

"We extract these two components (from mustard seed)," said Bletsky, who worked for about a decade for Novozymes, a Danish biologics company, before joining MustGrow. "When you combine them together and you add water, they create a natural active called AITC (allyl isothiocyanate)."

On its website, MustGrow says AITC can be used to control crop pests, weeds and pathogens that cause diseases, such as fusarium, botrytis, rhizoctonia and pythium.

The company has been around for about a decade but it was initially known as MPT - Mustard Products and Technologies.

New investors came in a couple of years ago, rebranded it as MustGrow Biologics and took the company public in July 2019.

MustGrow already has a registered granular version of its signature bio-pesticide, AITC. But it plans to register a liquid product and focus on sales to horticulture producers.

"The liquid version has a lot better cost and opens up more markets for us," said Bletsky, who grew up on a farm in eastern Saskatchewan. "The big market is definitely fruit and vegetables."

They also plan to test AITC on clubroot, to see if the bio-pesticide can control the soil-borne disease that threatens canola production in Western Canada.

Research has clearly shown that AITC can control disease pathogens and other crop pests, Bletsky said.

But he acknowledged that bio-pesticides have shortcomings.

"Our product on broad acres, corn, soybeans, canola, wheat… it would work but really it's not economical," he said. "Bio-pesticides and bio-control have a lot more opportunity, initially, in high value crops."

In addition to cost, certain bio-pesticides are finicky when it comes to storage. Some products must be kept at 4 C.

"Most of the warehouses (for ag retail) do not have refrigeration," Bletsky said.

There are other challenges. Such as, can they perform in real world conditions — when it's hot, dry, wet, cool or windy?

"In the commercial world, things are a lot more complex," said Gary Peng, an Agriculture Canada plant pathologist in Saskatoon.

Peng began studying bio-fungicides about 35 years ago, mostly on greenhouse and horticulture crops. He was convinced they could compete with traditional fungicides.

"At that time, the hypothesis was that the biocontrol would be able to replace a lot of chemicals," he said. "(The) initial results (were) very exciting."

In the late 2000s, Peng wanted to know if the bio-products could reduce clubroot symptoms on canola plants. To test out that theory, he selected a couple of registered bio-fungicides and applied them to the soil.

The performance in the greenhouse was fantastic.

In the field, the bio-pesticides flopped.

"I conducted about 11 field trials (and) tried different formulations. In-furrow spray, seed treatment and granular," he said. "Unfortunately, 10 of the 11 trials didn't show any positive results (for) clubroot control."

A factor may have been dry soil conditions. The bio-fungicide didn't survive long enough in the soil to have an impact on the clubroot spores.

The one positive result was on a vegetable crop in Ontario.

"The rain came the day after seeding… and there was irrigation. It was almost the perfect conditions for the treatment to perform."

Peng realized, after the research, that bio-pesticides may be impractical on big acreage farms.

"It tends to be more expensive to produce, more expensive to apply and more complicated to apply," he said. "In the spring, the growers are racing with the time to get the seeding done. If you need to modify the procedure too much… it's very difficult for growers to adopt any of those new technologies."

Bio-pesticides cost more and the volume of product can be significantly larger than traditional chemicals, but they can work on a 7,000 acre grain farm, Bletsky said.

Instead of treating an entire field with a bio-pesticide, it could be used to spray a troublesome patch, he said.

For example, it could be used on a problem area where a grower is struggling with clubroot, or another disease like aphanomyces root rot.

"It's not a one-shot wonder. It's another tool for farmers," he said. "To break up resistance. To (introduce) another mode of action."

Growers of canola, wheat and other big acreage crops need solutions that are effective and simple to use. Plus, if bio-pesticides need "Goldilocks" weather conditions (not too hot, or dry, or cold) to be effective, that's a huge limitation for Western Canada.

"We have had some bio-control successes, but it's obviously limited in terms of species… and dictated by the environmental conditions," Swanton said.

When it comes to insects and diseases, crop genetics are the easiest way to deliver pest control, Peng said.

The crop has built-in resistance to a particular disease, such as blackleg in canola, and it's extremely simple to use because growers plant the seed, just like any other seed.

Maybe, bio-pesticide seed treatments could work in tandem with genetic resistance, Peng added.

"If you can prime the seed to help the genetic resistance, that's where probably we need to look at…. The seed (treatment) might be where we can look at the synergistic effects with the genetic resistance."

Baerson, the USDA scientist in Mississippi, is pursuing the crop genetic path.

He has pinpointed the genes and enzymes that sorghum uses to produce sorgoleone, the natural weed killer, and has transferred the genetic package into rice.

He is also working with University of Wisconsin scientists to move the genes into corn, soybeans and wheat.

Eventually, Baerson's research could lead to crops that produce their own herbicide.

The technology isn't perfect, but it is promising.

"Bio-pesticide producing plants. It's hard to envision it eliminating all requirements for pesticides," he said. "But it should significantly reduce the amount."

Over the next 10 years or so, bio-pesticides will be used in tandem with synthetic pesticides and could replace them for certain situations, Bletsky said.

In the longer term, 15-20 years from now, a lot depends on public sentiment.

If consumer hostility ramps up and there are more legal threats to chemical pesticides, bio-pesticides could supplant synthetics.

"If you think of Syngenta and Bayer, both those organizations are investing billions into natural (and) bio-pesticides," Bletsky said. "Over the long-term, you are going to see new things (products) and that cost come down."

Source: Ag News

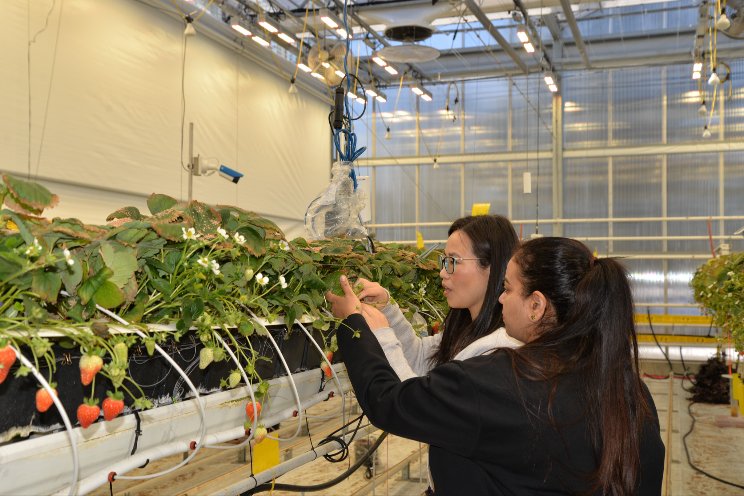

Photo Courtesy of Inside Battelle

Source: Ag News

More news